Through its successful mangrove-based carbon credit project in Sindh, Pakistan shows it can create opportunities for conservation of forest ecosystems for global climate benefits.

Climate change concerns are the predominant part of international environmental policy debates at the Conference of Parties of major global environmental conventions organised under the aegis of United Nations. These policy discussions revolve around enhancing national actions to reduce the increasing levels of greenhouse gas (GHG)emissions by reforming the current production and consumption patterns and promoting nature-based solutions to limit the warming of planet beyond the tipping point. The Paris Agreement 2016 under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) encourages the Parties to adopt low carbon strategies for climate change mitigation by limiting the global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius (2.00 C) while encouraging the efforts to limit the rise in temperature it to 1.50 C as compared to preindustrial level[i].

Potentially, forest ecosystems sequester one-third of global carbon emissions, besides providing a multitude of ecosystem services to support the livelihoods of 1.6 billion people around the world. Forest ecosystems are the largest terrestrial carbon sinks, absorbing roughly 2 billion tonnes of CO2 each year.[ii] Among forest ecosystems, mangroves are regarded as one of the world’s most productive ecosystems, occupying approximately one-fourth of the world’s tropical coastline, covering an area of between 167,000 square kilometres (sq km) and 181,000 sq km, in 112 countries (Spalding et al., 1997; Kathiresan & Bingham, 2021 in IUCN 2008)[iii]. Approximately, 40 per cent of mangroves occur in South and Southeast Asia, with the Sundarbans, spread over Bangladesh and India, having the single largest tract of mangroves in the world, extending over 600,000 hectares.

Mangroves comprise salt tolerant plants occurring naturally in sheltered coastal areas, such as river estuaries, creeks, backwaters, lagoons and bays where freshwater meets the seawater – in the intertidal transition zone between the land and the ocean.

In Pakistan, mangroves are most abundant in the Indus Delta, which constitutes 97 per cent of the total mangrove cover found in the country, whereas the remaining 3 per cent naturally occurring mangroves exist at three locations at Miani Hor, Kalmat Hor and Jiwani along the Balochistan coast. At few other locations in Balochistan, small patches of mangroves have been created artificially. The sediment-laden freshwater flows of the mighty Indus support large chunks of the thriving mangroves ecosystem in the delta. However, the hydrological imbalances due to reduction in freshwater inflows into the deltaic areas has altered the diversity of mangrove species due to increasing salinity levels. As such, of the original/ reported eight mangrove species found in the Indus Delta, four species have become extinct due to increasing salinity levels. As such, salt tolerant Avicennia marina is the most dominant species occupying over 90 per cent of the mangrove cover; three other species, Rhizophora mucronata, Ceriops tagal and Aegiceras corniculatum grow in few areas. All mangroves along the Pakistan coast now enjoy protected status under the forestry legislation in the Sindh and Balochistan provinces.

Ecological and social importance of mangrove ecosystem

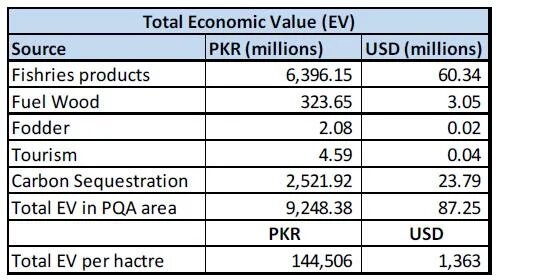

Mangroves are considered as one of the richest blue carbon ecosystems because of their ability to store large amounts of carbon in biomass, soil and dead roots. On average, they contain 937 tonnes of carbon per hectare per year (tC ha-1)[iv]. In addition to their high carbon storage and sequestration potential, mangrove ecosystems provide a multitude of other ecosystem services for coastal economies. They protect shorelines and act as the nature's shield against cyclones and coastal disasters, and as breeding grounds for a variety of fish and shrimp species. In one of the studies in the Port Qasim Area of Sindh, the economic values of mangrove ecosystem services have been assessed to be US$1,363 per year (Table 1)[v].

Mangroves and climate change

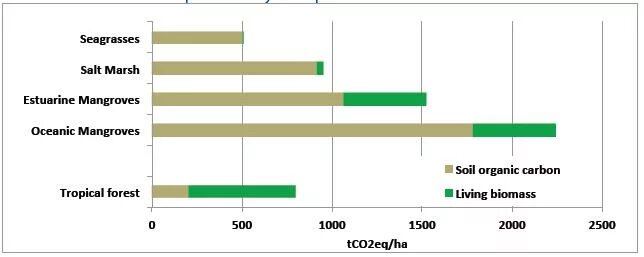

Globally, mangroves sequester approximately 1 per cent – 13.5 giga tonnes – of the total carbon sequestered by the world’s forests every year[vi]. Hence, they are one of the prime ecosystems for reforestation projects. On average, each hectare of mangroves sequesters 6 to 8 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. The carbon sequestration rates of mangroves are about two to four times higher than global rates observed in mature tropical forests (Table 2). Therefore, restoring or regenerating mangroves has significantly higher potential to sequester and store carbon than tropical forests. The tropical Asian mangroves are believed to contain larger biomass carbon of 563 tonnes carbon dioxide equivalent per hectare (tCO2e/ ha) than the subtropical stands that store 237 tCO2e/ ha. Among carbon pools, 50 per cent to 90 per cent of the total carbon is stored in mangrove soil; the rest is in living biomass. They also store more carbon in soil[vii]. A recent study conducted in Pakistan has estimated carbon density of 238.85 tonnes/ ha in mangroves, including soil carbon[viii].

Globally, an estimated one million hectares of mangroves have been lost since 1996[ix], highlighting the urgent need for action to protect these vital ecosystems to preserve carbon stocks and sustain their role in climate change mitigation. The main drivers behind this loss include urban expansion, aquaculture, mining, and overexploitation[x]. A hectare of lost tropical mangroves may release to the atmosphere GHG emissions as much as three to five hectares of tropical forest in the Amazon and upland areas of other tropical regions (IPCC 2007; Malhi 2009).

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement 2016 provides opportunities of voluntary cooperation among countries to support implementation of their commitments of nationally determined contributions (NDCs); in particular the Article 6.2 encourages transparent and accountable international transfer of mitigation outcomes (ITMO) among the countries.

National policy context

Considering the low-hanging fruit, nature-based solutions are an integral part of climate change mitigation and adaptation policies and strategies and NDCs of Pakistan. The updated National Climate Change Policy 2021 and its Implementation Framework (2014-2030), National Forest Policy 2017, National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2017 envisage conservation and sustainable management of forestry resources for climate mitigation and resilience building.

Constitutionally, forestry is a provincial subject with dedicated provincial forestry departments responsible for their protection, conservation and management. However, any international transaction pertaining to trading of carbon credits essentially requires a no objection certificate from the Ministry of Climate Change and Environmental Coordination (MoCC&EC), which is the national designated authority responsible for preparing and maintaining national GHG inventory under the UNFCCC. Such no objection certificate is required for avoiding double counting of carbon emissions or removal so as to ensure transparency of carbon credit transfer.

Therefore, in order to regulate transparent mechanisms and promote access to carbon markets, the MoCC&EC is finalising the Policy Guidelines for Carbon Trading, in addition to supporting national capacity building and development of sectoral Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV) standards. These regulatory frameworks are expected to create avenues of generating climate finance to support climate change mitigation and adaptation actions by harnessing financing opportunities under emerging carbon markets, including accessing result-based payments (RBPs) through the implementation of REDD+ (Reducing Emission from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) in line with Article 5 of the Paris Agreement. The recently established Pakistan Climate Change Authority further supports the institutional mechanisms to explore financial instruments to bridge the gaps in climate finance needs for mitigation and adaptation in Pakistan, which are estimated to be US$392 billion[xi].

Mangrove restoration drive and carbon credits

The restoration of mangroves along Pakistan’s coast has been progressing since late 1980s, resulting in a 300 per cent increase in mangrove cover since the 1990s and making it the only country in the region with an expanding mangrove cover. The restoration work has gained significant momentum during the last two decades mainly through support of public and donor funding, including provincial governments of Sindh and Balochistan, the federal government, World Bank, Asian Development Bank and EU. Large scale restoration of mangroves has occurred in the Indus Delta since 2009 and has continued since then through provincial and national public funding.

“Carbon finance through the private sector has helped us a lot in achieving the yearly afforestation and reforestation targets under the DBC-I (Delta Blue Carbon Project-1) as compared to relying on budgetary allocations through public financial procedures. It is timely, efficient and transparent to tackle restoration programmes in the country,” said Riaz Ahmed Wagan, Chief Conservator of Forests, Sindh.

While the development of national institutional mechanisms and capacities continue progressing, Sindh has been the first province in Pakistan to pioneer mangrove credits transactions in the voluntary carbon market under the DBC-I. The initiative is the world's largest mangrove restoration project with an expected carbon sequestration potential of 127 million tCO2e over its lifetime, targeting protection of 125,000 ha and afforestation/ reforestation of 225,000 ha. The project is expected to generate socioeconomic co-benefits for 42,000 people living in 60 villages of the project area.

The DBC-I project constitutes the first ever forest carbon project in Pakistan initiated under the public-private partnership between the Government of Sindh through Sindh Forest Department and the Indus Delta Capital, a local subsidiary of an UK based private company. The proposed sharing of carbon credit sale amount is 60 per cent and 40 per cent among private partners and the Government of Sindh, respectively.

The project received highest political support from the Government of Sindh. The public-private partnership process started with Merlin’s Wood, a UK based private company for development of carbon projects, showing an interest in it. Subsequently, in 2013, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the private company and the Sindh Forest Department. It was followed by the signing of an agreement in 2015 with the approval of Chief Minister, Sindh. The feasibility assessment and field studies for developing a project description document (PDD) from 2015 to 2018 was done with an initial investment by the private partner. The PDD was finally submitted in 2019 for registration to Verra, an international voluntary market registry of carbon projects. Verra is leading the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) for climate action and sustainable development and has issued more than 1.2 billion verified carbon units from more than 2200 projects in 95 countries around the world[xii]. The PDD followed Afforestation, Reforestation and Revegetation (ARR) and Restoring Wetland Ecosystems (RWE) project standards and was validated by Verra in March 2020[xiii].

“It is time for the developed nations to pay back to the developing nations by investing in nature-based solutions, especially restoration of ecosystems like mangroves and other tropical and subtropical forests, which need resources for conservation. The methodologies for protection, improved forest management and new forests development for carbon finance may be broadened to the level that they help in qualifying the majority of protection and restoration efforts for monetisation,” said Wagan, Chief Conservator of Forests (Mangroves), Sindh.

The first monitoring report of the project was generated in 2021, but the verification was delayed due to COVID-19 pandemic. The first tranche of verified mangrove carbon credits was issued by Verra in March 2022 and the credits were sold in December 2022 against which the Sindh government received US$14.747 million as their share as per the agreement. The second project monitoring report has been submitted to Verra for verification and issuance of carbon credits, which is under process.

As the national designated authority, the MoCC&EC has facilitated transfer of ITMOs generated under the project with the approval of the cabinet during 2022. In order to streamline the private sector finance through carbon markets, the MoCC&EC has formulated Policy Guidelines for Carbon Trading to establish an institutional and regulatory framework for such transactions, which are under process of approval.

Following DBC-I, The Government of Sindh signed an agreement for DBC-II with Caelum Environmental Solutions in 2020. Sindh has also initiated feasibility studies of forest carbon projects for riverine forest ecosystems. Emulating Sindh, other provinces such as GB, KPK and Punjab have also initiated the process of feasibility studies for developing forest carbon projects for their respective forest ecosystems. The Indus Delta Blue Carbon project has set an example of harnessing climate finance opportunities that exist in the evolving carbon markets to support implementation of national climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Apart from voluntary markets, reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, conservation, enhancement and sustainable management of forest carbon stock under Article 5 of the Paris Agreements also provides opportunities for countries to access performance related result-based payments. REDD+ mechanism acknowledges carbon credits generated through jurisdictional-scale avoided deforestation projects; however, accurate estimation of robust baseline deforestation emissions is a big challenge in such projects[xiv]. Besides, multi-donor trust fund, such as the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility managed by the World Bank, and LEAF Coalition (Lowering Emissions from Accelerated Finance) also provides opportunities for trading of high integrity carbon credits by private sector buyers from forest countries (national and subnational level), which have implemented jurisdictional REDD+ programmes to reduce deforestation[xv]. Such credits are required to meet The REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard (TREES) and are issued by Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), which is a global initiative for incentivising governments to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation as well as restoration and protection of forests[xvi].

Conclusions and recommendations

Climate change is at the centre of global policy debates among the parties to the UNFCCC. The Global Stocktake (GST) has significantly emphasised on enhancing global efforts toward halting and reversing forest loss and degradation by 2030 to achieve the Paris Agreement temperature goal and accelerating the use of ecosystem-based adaptation and nature-based solutions to mitigate climate impacts. Mangroves constitute one of the important coastal ecosystems for their significant ability to store and sequester atmospheric carbon for climate mitigation and the associated adaptation co-benefit that support building resilience of coastal communities against the climate induced extreme events.

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement entails carbon markets to facilitate cooperation among the countries to achieve their NDC commitments. Such markets also create financial value of the carbon stored in trees and forests to incentivise the developing countries to conserve carbon in their forests, and also market the generated carbon credits to the interested buyers in developed countries as ITMOs in a transparent manner.

Relatively, carbon markets are new for the countries like Pakistan; however, they offer excellent opportunity for scaling investment in forest carbon results and credits, with mangrove restoration project in the Indus Delta acting as catalyst for the excellent opportunities that lie ahead in carbon markets to incentivise conservation of other forest ecosystems. At the country level, the institutional and regulatory frameworks require further streamlining to facilitate the process of harnessing the opportunities provided by carbon markets for generating climate finance, as well as supporting the broader national and international objectives of climate mitigation and adaptation.

ENDNOTES:

[ii]United Nations 2021. The Global Forest Goals Report 2021.

[iv]Daniel M Alongi (2012) Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests, Carbon Management, 3:3, 313-322, DOI: 10.4155/cmt.12.20

[v]IOBM 2016. Valuation of Mangroves in PQA Indus Delta: An Econometric Approach

[vi]Daniel M Alongi (2012) Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests, Carbon Management, 3:3, 313-322, DOI: 10.4155/cmt.12.20

[vii]Daniel M Alongi (2012) Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests, Carbon Management, 3:3, 313-322, DOI: 10.4155/cmt.12.20

[viii]MoCC 2022. National Forest Cover Atlas.

[x]Daniel M Alongi (2012) Carbon sequestration in mangrove forests, Carbon Management, 3:3, 313-322, DOI: 10.4155/cmt.12.20

[xi]MoCC&EC 2023. National Adaptation Plan - Pakistan

[xiii]Riaz Ahmed Wagan, Chief Conservator of Forests, Sindh Forest Department (personal communication).