The mushrooming growth of housing societies on agricultural land in Pakistan endangers its food security.

There was a time when Pakistan was not only self-sufficient in food supplies but also exported farm products. But unfortunately, this is not the case anymore. Pakistan is now importing wheat, cotton, sugar and other farm products. The country’s food import bill rose by over 15.46 per cent to $7.06 billion in the first nine months of the Financial Year 2022 from $6.12 billion in the corresponding period last year to bridge the gap in food production.

Pakistan was an agrarian economy at the time of its inception and the agriculture sector contributed sufficiently to its economic growth. According to World Bank, in 1960, the contribution of the agriculture sector to Pakistan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was 43.2 per cent. However, the sector’s share in GDP has decreased over the years. Presently, its contribution to GDP is 23 per cent.

Pakistan’s food shortages

In the year 2021, Pakistan was ranked 92nd out of 116 nations in the Global Hunger Index (GHI). Pakistan was better positioned as compared to India, which ranked 101 on GHI. However, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, two other close regional neighbours, outshined Pakistan with 76th and 65th positions respectively.

There is no doubt that Pakistan as an agricultural country failed to improve the yield capacity of principal crops and there are lower per acre yields as compared to those in other countries. Farmers blame absence of efficient, new seed varieties, intermittent water supply and lack of government support in terms of support prices for crops for lower per acre yield. Global warming and climate change too are being blamed for growing food shortages in Pakistan.

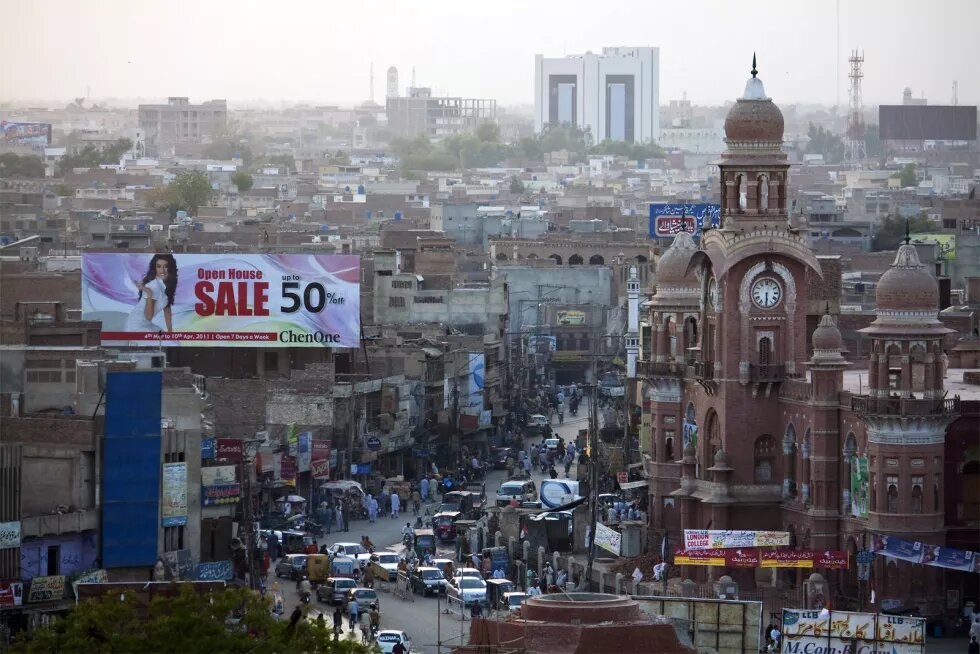

However, a very important factor has escaped due notice as far as Pakistan’s food problems are concerned – the mushrooming growth of housing societies. Real estate business, which is among the most lucrative economic activities in the country, is eating up the farmland. The green, fertile patches of agricultural land are now in the hot-selling category of real estate business ventures.

Targeting fertile land

In June last year, pictures and videos of felled mango trees, some of them loaded in trucks as logs, went viral on social media in Pakistan. Ostensibly, the destruction of the trees was meant to make way for a private housing project. It triggered an intense debate on the issue of conversion of fertile farmland into housing societies and its impact on environment and food security in the future. Twitterati including politicians and activists condemned the decimation of mango orchards and urged the authorities to halt it.

Subsequently, the Government of Punjab ordered an inquiry into the incident. The report confirmed that the trees in the mango orchard on an area of about 12 acres were cut down and wood logs were found at the site.

“I have seen an exponential growth in housing societies in my area,” says Adam Saeed, a resident of Qadir Pur Rawn near Multan city in the Punjab province. “People are either selling their farmland to property developers or developing their own housing societies.”

According to him, property developers pay very good money; an acre of land now can fetch a farmer more than Rs.20 million. “Farmers want to sell their farm land and start some business. They complain that agriculture is not that profitable now,” says Saeed.

Multan is known worldwide for producing the best quality mangoes. But now Saeed fears that one day all mango orchards will be converted into housing societies. “Thousands of acres of farmland around Multan have been converted into housing societies. One of the housing societies acquired 12,000 acres of mango orchards to build a residential society,” he said.

The Lahore High Court has ordered the authorities to stop the construction of illegal housing societies on the agricultural land following a petition in this regard. According to the petition by the Kisan Board Pakistan, a non-governmental agricultural advisory and research organisation, housing schemes have so far eaten up 20-30 per cent of the fertile land in Punjab province. In Lahore alone, 70 per cent of agricultural land has been converted into gated housing societies. Faisalabad has lost 30 per cent of its fertile land to real estate developers. Other cities of the province could also not have escaped this grim phenomenon. “We went to the court against the development of housing societies on fertile agricultural land and the court ordered the government to stop it,” says Shukat Ali Chaddar, President of Kissan Board Pakistan.

However, despite the halt by the court on their activities, builders have somehow found ways to continue building societies on farmland. Chaddar says that Pakistan is already importing wheat, sugar and edible oil and if it continues to allow conversion of fertile land into housing societies, then the future looks scary. “Travel on any major road in Punjab and see how fast housing societies are developing on fertile agricultural land, and most of these societies are illegal. The government needs to take serious steps now and implement the court's orders in letter and spirit. Mere serving notices and issuing advisories won't solve the problem,” he says.

In December 2020, Pakistani media reported that over 69 per cent of the country's housing societies were not registered with government institutions. Official documents reveal that out of a total of 8,767 housing societies, 6,000 are not registered with the concerned institutions. These 6,000 housing societies have been made on bogus or incomplete papers. In Pakistan’s capital city of Islamabad, there are 146 illegal/ unauthorised housing societies. It is mandatory for housing societies to register themselves with different government organisations and get no objection certificates (NOCs). However, many developers start developing societies and selling plots before obtaining these NOCs. It is unfortunate that government departments have failed to take strict action and stop this practice. They let it happen and once such illegal works get started, it is usually very difficult to stop as developers go to courts and bring stay orders against government actions.

Arif Hassan, a Karachi based urban planner and architect, believes that the proliferation of housing societies on farmlands is a direct result of the complete failure of the state authorities. ”Institutions, which are supposed to protect land, are corrupt and facilitating property developers in developing new housing societies. We need to protect land use plans. All big cities have land use plans but unfortunately state authorities are not implementing and enforcing these plans,” says Hassan.

According to the law, housing societies are bound to provide all basic civic facilities like electricity, roads and sewerage to its residents and one gets these in housing societies like Bahria Town or Defence Housing Authority. But unfortunately, these societies are so expensive that a middle class person cannot afford to build a house there. A five-marla plot in these societies costs more than Rs.8 million (a marla equals 272.75 square feet). Compared to these approved housing societies, land is much cheaper in illegal housing societies.

“Land is much affordable in illegal housing societies for common man. But such societies offer almost nothing in terms of basic civic facilities. I know of a housing society in Islamabad that has more than 300 families but none of them have proper access to electricity. They all depend on a few electricity meters installed in the society,” says Nayab Khan, who works as property consultant in Islamabad.

Demographic challenges

According to the World Population Prospects 2022, Pakistan's already high population of over 220 million people will rise to 366 million by the year 2050 – an increase of 56 per cent. Pakistan is now the fifth most populous country in the world, a steep climb over the last few years from being the eighth.

A country with a population of over 220 million people and population growth rate of 2 per cent needs housing societies. “There is no doubt that Pakistan needs housing societies for its growing population but it cannot build these on fertile agricultural land. It's a matter of food availability for coming generations,” says Shukat Ali Chaddar.

He says that Pakistan has 10.8 million acres of cultivable land available, which are not under cultivation. Authorities need to make policies and build new cities and towns on this land instead of letting people build housing societies on land, which is already under cultivation, he adds.

Arif Hassan says that there is definitely a pressure of population growth and Pakistan needs housing but still there are many ways to protect farmland. “We are destroying our fertile land. Pakistan needs to have a land limitation law immediately. The government must come up with a law and not let anyone build a house on more than 500 yards. This way we can protect our agricultural land,” says Arif Hassan.

Lucrative property business

In Pakistan, investing in property is a very lucrative business for real estate companies and individuals as well. There is a perception that investing in property can get high returns in a short period of time. In July 2020, former Prime Minister Imran Khan announced a package for the construction industry and launched the Naya Pakistan housing scheme. The government at that time said that people investing in the construction industry would not be asked about their sources of income.

The government’s aim at that time was to kick-start the economy through the construction industry to tackle COVID-19’s economic challenges. It was a good move by the government at that time but with bad results. Most people started buying properties instead of investing in construction. The package, in fact, triggered a boom in the property sector. “It’s a good business with good returns. There was massive activity in the property sector after the last government’s package. Suddenly new societies appeared, some legal and other illegal, but definitely on farmland around Islamabad,'' says Nayab Khan.

Arif Hassan is very critical of the last government’s construction package. According to him, it did nothing good to the economy instead it increased speculation in the property market. “People invested heavily in property just to convert their black money to white and this led to the development of new societies. People have bought plots and that’s it. There will be no construction on these plots for years. But there will not be any farming on the land either. Governments need to end speculation in the property market,” says Hassan.

Challenges ahead

There is no doubt that population growth in Pakistan poses serious challenges for generations to come – taking care of housing for all as well as saving fertile land for food security.

“Pakistan needs to impose a non-utilisation fee on property. I have seen societies in cities like Faisalabad and Gujranwala where people have yet to initiate any construction activity on land purchased many years ago. Pakistan can’t afford this. Bahria Town Group is building a huge gated housing society in Karachi. It is claimed that 3 million people will live in this society. I doubt it. People will just purchase plots and that’s it. Non-utilisation fee will help in ending this trend of buying plots and leaving them for years without using them,” says Arif Hassan.

Housing societies developed years ago on agricultural land are lying empty for years now without any construction activity. There are no signs that in near future people will come and live there. It’s a waste of agricultural land.

For Shukat Ali Chaddar, the state has the most important role to play if food availability for future generations of Pakistan has to be secured. “It's the state’s responsibility to save fertile agricultural land. State must remove lacunas in the existing laws and strictly implement it. We will keep raising our voices and go to every forum available. It is a matter of life and death for our future generations,” he says.

It is mango season in Pakistan and Adam Saeed draws satisfaction seeing his mango orchard bearing fruit. “You know, it takes three generations to get fruit from a mango orchard. My grandfather cultivated our mango orchard. He knew every single tree in the orchard as the back of his hand. He didn’t last long to see the quality of the mangos of his orchard, which he cultivated with all his love,” Saeed says.

However, now a huge housing society is developing next to his orchard. People are advising Saeed to convert his orchard into a housing society because it will fetch far better income than what he is earning from his orchard right now. “I will never turn my orchard into a housing society. I have everything I need and this orchard reminds me of my elders and their struggle,” the mango farmer says.

But how many orchard owners can resist the temptation of big money and save their fertile agricultural land like Saeed? Pakistan needs many more like him to secure the future generations as far as food availability is concerned.