The story narrates ordeal of artist community of Afghanistan who are in deep crisis after toppling of Afghan government by Taliban. Almost all musicians and melody performers in Afghanistan abandoned their profession and went into hiding to escape Taliban’s wrath. Those who could manage fled their motherland for new destinations including Pakistan for life safety and to continue the art liked by them as a passion. The story brings into light hardships of Afghan artists, especially financial quagmire, they are faced with after migrating Pakistan.

Escaping Taliban’s wrath - Fleeing Afghan musicians land in deep financial abyss at Pakistan

Ajmal Khan, a 28-year-old Afghan musician, fled Afghanistan to escape the Taliban’s wrath due to their radical religious stance on music, and also to continue the art he opted for as a passion. He landed in Pakistan’s border city of Peshawar.

“I reached Pakistan in the first week of September 2021 to ensure safety to my life and also to save my source of livelihood, music, which is very much dear to me,” says Ajmal while speaking to me at a melody studio in Peshawar.

Located at a road travel distance of around 289 km from Kabul, Peshawar is currently sheltering around 40 Afghan musicians like Ajmal, including two women, who fled their native country almost empty-handed soon after the Taliban took over Afghanistan.

Around the same number of musicians from Afghanistan took refuge in the Pakistani city Quetta by crossing the Chaman border, which is located in the in the southeast of Afghanistan and leads into Baluchistan province.

“If Pakistan lifts its restriction on refugees’ arrival, hundreds of artistes stranded in Afghanistan will migrate here to get asylum,” Ajmal claims.

The US forces completed their withdrawal from Afghanisthan on 30 August. In the changing scenario after the withdrawal, the Pakistan government decided to close its borders for refugees due to lack of its capacity to shoulder further burden. However, border restrictions are relaxed for patients who are allowed to enter for the purpose of treatment in healthcare facilities.

“Since the last four decades, Pakistan has been hosting around 1.4 million Afghan refugees who have been registered in 2006 and provided with Proof of Registration (POR) cards to benefit from schemes offered by United Nations High Commissioner for Afghan Refugees (UNHCR),” says Qaiser Khan Afridi, spokesman of the UN agency in Pakistan.

On the other hand, Qaiser says, approximately 850,000 more Afghan nationals who did not get themselves registered as refugees were provided Afghan Citizen Cards (ACC). However,

ACC card holders do not come in the mandate of UNHCR, he adds.

Ajmal, who has been associated with music since he was a 10-year-old, specialises in playing the tabla (twin hand drums). “Music is my soul I did not want to disassociate myself from my passion,” he says.

Ajmal says that like the majority of musicians in Afghanistan, he had to hide himself and his instruments after the Taliban took over as he was haunted by the radical group’s notoriety for ill-treating artistes and strictly prohibiting music during their earlier rule from 1996 to 2001. In his home in Jalalabad, the capital of Nangarhar province, local Taliban fighters searched and ransacked melody studios, raided offices, and piled up instruments to set them ablaze, spreading fear among community members.

Soon after the consolidation of control in Afghanistan, Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid in an interview with The New York Times on 26 August stated that “music is forbidden in Islam”, indirectly conveying the message to artiste communities that they were now being considered as persona non grata in their own country and can no more continue with their vocation.

Ajmal says: “After few days of hide and seek and on hearing news that Taliban are raiding music studios across the country, I realised that I have no other option than fleeing to Pakistan.”

Ajmal and his ailing mother had to undergo a very treacherous journey of around 24 hours on rough terrain to enter Pakistan from the Spin Boldak border where people from both sides cross on a daily basis for business purposes. He had to pay a hefty amount of around PKR 100,000 (US $588) as travel expense and for crossing the border without a visa or relevant travel documents.

Financial stress in Pakistan

On reaching Pakistan, Ajmal and all his fellow artistes heaved a sigh of relief as they became free from fear of persecution on religious grounds. But they were faced with a new and much more serious challenge – severe financial constraints due to lack of work and a proper legal status.

“I am free to play music in Pakistan, but the problem is that I am empty-pocketed, not being able to earn an amount which could fulfill our family’s very essential needs of food, not to talk about arranging medicine for my mother and utility bills,” Ajmal says.

In almost two months’ stay in Peshawar, Ajmal claims he has hardly earned PKR 8,500 (US $50) whereas the monthly rent of his two-room home in Peshawar is PKR 15,000 (US $88) and the average monthly electricity bill is PKR 8,000 (US $47). According to him, all these expenses, including medicine for his ailing mother having kidney complications, is met through borrowing from relatives who live in Pakistan.

“The economic quagmire seems more severe to me than browbeating by religious fanatics and I fear that fight for survival will wither away my affection for music, forcing me to forsake the passion and opt for some other source of earning,” Ajmal bewails.

Zia Sahar, an Afghan singer from Ningarhar province, also had no other option except to rush to Pakistan for safety, leaving behind his spouse and five children including three patients of thalassemia, a serious affliction of blood disorder.

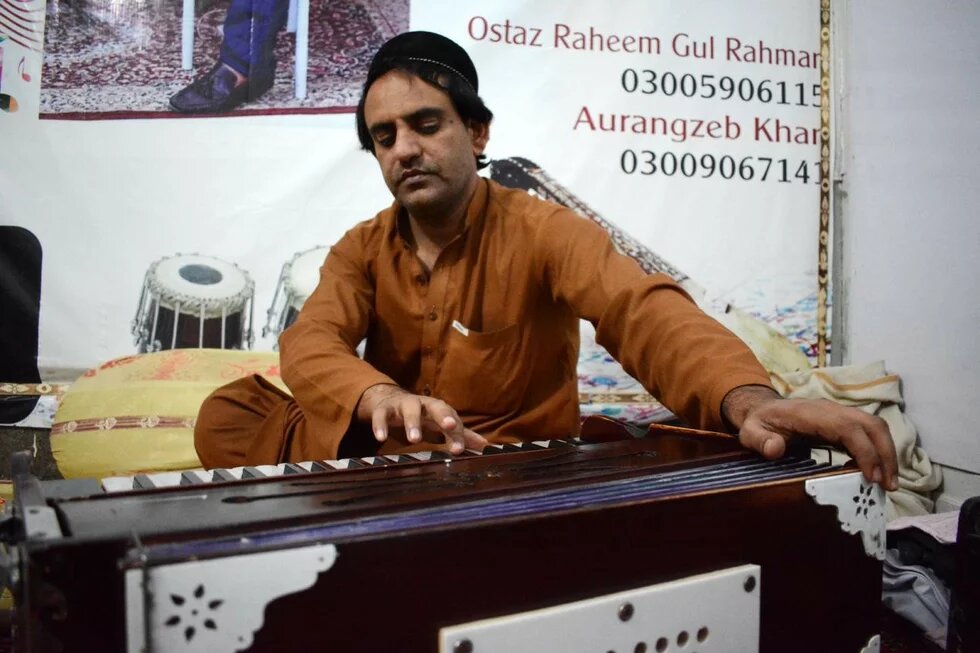

Afghan singer Zia Sahar playing harmonium during rehearsal at a music studio in Peshawar city of Pakistan where local musicians warmly received artistes fleeing from Afghanistan to escape the Taliban’s wrath.

“My group members and I were told by friends and relatives that the country’s constitution was changed and musicians were not allowed to perform. In fact, we were told that we may face the fury of Afghanistan’s new rulers if signboards from studios and instruments were not removed,” Zia tells me while rehearsing at a single-room music studio, which is also providing boarding facility to him.

“I had not enough resources to shift my whole family and migrated alone to Pakistan leaving behind my ailing children whose faces are always in front of my eyes,” Zia says with a chocked voice.

Zia sings songs in Pashto and Dari (Persian) languages. In Afghanistan, he normally earned 1,500 to 2,000 Afghanis – around PKR 3,000 to PKR 4,000 (US $ 17.64 to US $23.5) – on a daily basis through performing at events like marriage ceremonies and gatherings. Now in Pakistan, he hardly earns PKR 3,000 (US $17.64) to PKR 4,000 (US $23.5) per week. “It is quite insufficient to meet my personal expenditure here. How can I send money home for fulfilling my family’s basic requirements and for arranging blood change for ailing three sons?” explains Zia while holding tears in his eyes.

Zia, however, is full of praise for local musicians in Peshawar for allowing them to join their troupe and to accompany them to events on weekly basis through which they make some earning. Due to lack of travel documents, Zia and other artistes also have fear in mind of getting arrested by police, which usually intercept them on way back late night after performances at wedding gatherings and ask for identity documents. Fortunately, Zia says, he is still safe from getting detained over immigration laws violation due to intervention of local musicians.

Samar Gul, a harmonium player from Jalalabad, is highly concerned about education of his three school going children, including a girl who dropped out from school due to their inability to pay for tuition fee.

Samar paid 1,200 Afghanis or around PKR 2,400 (US $14.11) for each child as monthly fee for their studies at school. All of them have now dropped out of school. “The earning I am making after migration to Pakistan is hardly enough to fulfill very basic need of flour for my family to eat bread,” Samar reasons, his grim face clearly portraying his inner feeling of despair and despondency.

According to Samar, life of Afghan artistes and their families have become miserable after the change of rule in Afghanistan. He says that an Afghan music maestro, Khushal Taj, is now selling boiled kidney beans on a hand cart in his native city in Nangarhar province to eke out living.

The family of Muhammad Sami, another young Afghan artiste wearing traditional dress decorated with silk embroidery, has been associated with the music industry for centuries. Sami, who has inherited music from the elders in the family, is very much concerned about the instruments including rubab (a lute-like musical instrument), harmonium, hand drums, flute, which are heirloom of his ancestors, passing through generations. “I could not bring the instruments to Pakistan because of security concern and left them behind at home,” he says.

Sami says he has heard about general amnesty announced by the Taliban for everyone including their enemies, but cannot trust the local fighters who are extreme in their faith and can go berserk in a moment.

Sami’s fear proved true on 31 October when some Taliban fighters reportedly barged into a wedding gathering in Nangarhar. After heated altercations over music playing inside, they opened fire on the marriage party, turning a merry occasion into wailing funeral of two persons who died after receiving bullet wounds.

Warm welcome from Pakistani artistes

The artistes of Pakistan have stood by their Afghan counterparts in their distressing times. An organisation of Pakistan’s artistes, Hunari Toolana (artistes’ organisation), came to the rescue of fleeing Afghan artistes after the Taliban takeover of the country.

Rashid Ahmad Khan, president of Hunari Toolana, which has 1,600 artistes as members, says: “On hearing news about the takeover, I realised that it was a bad time for Afghan artistes. So on the very next day, on 16 August, I issued a statement that all the affected artistes were welcomed here in our country.”

Rashid tells me that he told his colleagues that they will give space to the distressed brethren from Afghanistan and share their earning with them so that they could survive at this difficult juncture of life. He has provided membership cards of Hunari Toolana to all the visiting Afghan musicians to ensure they are not harassed by the police.

The artiste community of Pakistan was also passing through financial complications due to one and a half years of COVID-19 preventive lockdown, restricting all kind of public gatherings and events, still it decided not to leave the Afghan counterparts alone in this time of trial. Hunari Toolana president Rashid also wrote a letter to the UNHCR requesting the UN body to extend assistance to Afghan artistes on humanitarian basis.

Rashid, who is doing his dissertation on “Critical Analysis of Pashto Music Tradition” criticised the Taliban for their radical views about musicians. “The renowned Islamic saints of this region have preached Islam through singing Sufi (mysticism) sayings. The presence of music in society ensures germination of peace and love among people,” believes Rashid.

Music ban hits Pakistani artistes too

Rahim Gul, an expert rabab player and head of his music teaching academy, feels that the ban on music in Afghanistan has impacted artistes in Pakistan too. Many Pakistani artistes used to perform in Afghanistan before the Taliban takeover.

Rahim says Afghans love classical and traditional songs and paid suitable amount to artistes for performing at events. “A number of our Pashto singers and musicians are quite popular in Afghanistan and were invited frequently to perform in different events, but now this activity has been totally stopped,” Rahim explains.

Arbab Fazle Rauf is an amateur singer and music adviser to Abaseen Arts Council, an art gallery founded in 1955 at Peshawar to host art, music classes and display work of visual artistes, performers and writers. He is of the opinion that not only musicians but the whole artiste community of Afghanistan including theatre actors, stage performers and even painters will be affected by restrictions by the Taliban on cultural activities. “Pashto music, cinema, drama and painting have a very long history involving thousands of people in this industry who now suddenly have become jobless,” Arbab Fazle says.

He says the Taliban should remember that the old Pashtun traditions and norms permeated in society due to its practices from centuries and cannot be eradicated instantly through use of force.

UNHCR’s assistance

UNHCR spokesperson Qaiser Khan Afridi says that they are deeply concerned about the plight of the affected Afghan artistes and are considering measures to extend assistance to them, but this is in very initial stage. “We feel their pain and are trying to help them in this time of need, but nothing is decided yet and it will take few days,” he says.

According to Qaiser, the UNHCR has requested regional countries to not deport asylum seekers, especially those who are vulnerable and would face difficulties on return to their homeland.

Religious background

“In Islam, prohibition on different practices came subsequently in phased manner making it easy for followers to obey,” says Abdul Ghafoor, renowned religious scholar and former director of the Sheikh Zahid Islamic Centre in Peshawar.

The professor said evil practices, which prevailed in society at the advent of Islam, were banned on faithfuls step by step. Since the Taliban are struggling to form an Islamic Emirate, they are not showing leniency to cultural activities to express their seriousness to the cause, he adds.

However, in light of Islamic injunctions, he continues, if Taliban are not willing to allow artistes to continue more with the profession, they (Taliban) should have to make arrangements for compensating the affected people and take measures for providing them some alternate source of livelihood.

Artistes are a part of society having families and children. They need reasonable earning to meet their daily requirements for which the Taliban should made arrangements on urgent basis, he says.