Emergence of diverse and inclusive Civil Society organizations, such as NGOs and associations are among the mentionable gains during the last two decades of Afghanistan history. NGOs run a wide range of programs including the promotion of Human Rights, education, health and livelihood initiatives. Nevertheless, beside increasing threats of insecurity, NGOs are constantly faced with challenges of laws and policies. The report investigates the implications of the most recent limiting changes on the NGOs and elaborates their impacts on the prospects of a free, and open space for Civil Society in the country.

Abstract: Emergence of diverse and inclusive Civil Society organizations, such as NGOs and associations are among the mentionable gains during the last two decades of Afghanistan history. NGOs run a wide range of programs including the promotion of Human Rights, education, health and livelihood initiatives. Nevertheless, beside increasing threats of insecurity, NGOs are constantly faced with challenges of laws and policies. The report investigates the implications of the most recent limiting changes on the NGOs and elaborates their impacts on the prospects of a free, and open space for Civil Society in the country.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Towards the GoNGOs in Afghanistan: a snapshot of the current situation

- Legislating a new NGO- law

- The status of non-governmental institutions in the laws of Afghanistan

- NGOs and recent legislations

- Undue times and process

- Renewal of the NGOs licenses

- The restricting rules

- Dissolution of NGOs

- Governance of the NGOs by interference in their internal management

- The Impacts of closing civic space on NGOs

- The draft NGO law and the obligations of Afghanistan under Human Rights Laws

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- The Constitution of Afghanistan

- Conclusion

- Sources

Introduction

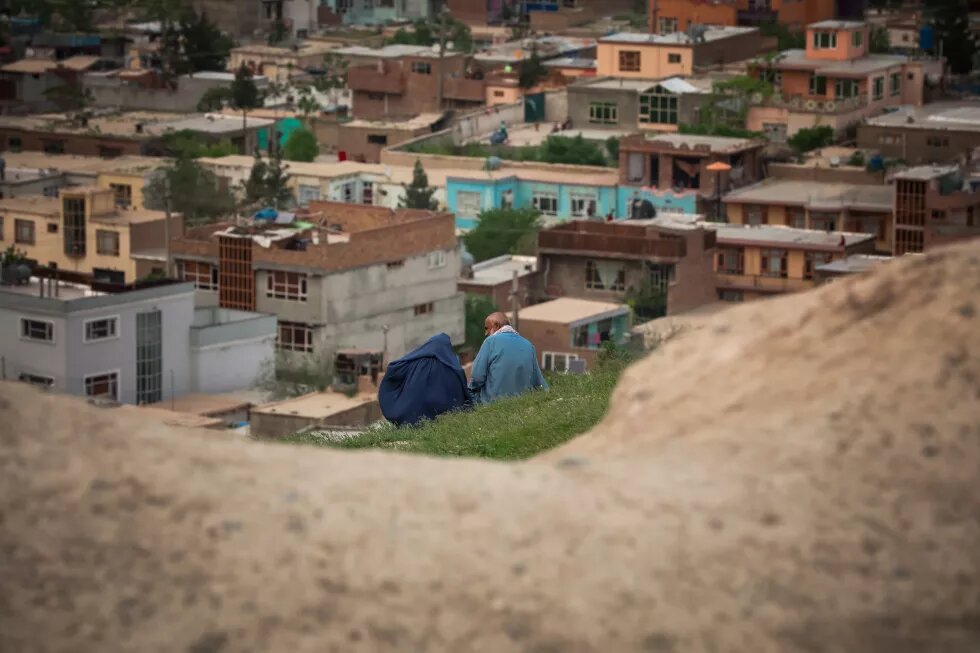

People in Afghanistan traditionally rely on customary councils and assemblies (Shuras and Jirgahs) in public places in order to discuss problems or represent their respective communities’ or groups’ interests. These traditional councils are launched frequently at various levels, ranging from a village to national levels. In some occasions, up to thousands of people from all over the country participate in such gatherings, where decisions on major national political agendas are made. These include for instance passing the new constitution in 2004, and most recently, endorsing the government’s peace strategy on 9 August 2020. Beside these traditional civic councils and groups, registered civil society organizations also have deep roots in the country’s modern history. Around a century ago, scholars and social elites who promoted constitutionalism, established a few non-state organizations, including Anjoman-e Adabi Kabul (The Kabul Literature Association).

The start of the civil war in the late 1970s provided a unique atmosphere for the emergence and growth of non-government organizations (NGOs) that have provided significant basic services and maintained a minimum of the infrastructures in the war-torn county. During that time, NGOs received substantial financial aid from UN agencies, such as the World Food Programme (WFP), and other funders, such as USAID. In January 1990, the Afghan government ratified a law that officially permitted NGOs’ operation in the country.

Today, the Ministry of Economy regulates NGO policies and reports that NGOs effectively bridge the gap of providing services in the remote and insecure areas of the country, where people have no or very limited access to basic services, such as health, education, agriculture, social protection and other infrastructures. A detailed report from Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) shows that the NGO programs run most of the supports and services in districts that are contested or under Taliban control.

Since 2001, international donors increasingly pledged for financial aids and the number of NGOs significantly increased. In 2005 the Afghan state enacted and amended a Law on Non-Governmental Organizations. This law defines an organization as follows:

- A domestic non-governmental organization, which is established to pursue specific objectives (Article 5.2);

- A foreign organization entity, which is established outside of Afghanistan (Article 5.3);

- An international foreign organization, which is established outside the country and operates in more than one country (Article 5.4);

- A nonprofit approach (Article 5.5).

According to the mentioned law, establishing an NGO as a legal entity is subjected to the approval of the Ministry of Economy, which issues Certificates of Registration for the NGOs, allowing them to commence their activities.

By emergence of the democratic state in the country in 2001, Donor communities have granted funds for nation-building initiatives, which has consequently led to NGOs and other civil society1 adjusting their strategies towards implementing projects that included, civic education, greater political actions and advocacy. For example, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), a Kabul-based independent research institute, observed that monitoring of authorities and promoting of good governance has been one of the critical initiatives by NGOs in recent years. Some observers mark such contributions as a phased change in the role of NGOs from “implementing agencies to facilitators of participatory community” (for more detail see here).

Afghan civil society suffers thus, from this limiting trend. Besides the growing number of NGOs, the government attempted to continuously intervene and apparently enforced many limiting measures in an ever-growing power struggle. Danny Singh, a researcher at Teesside University, maintains that this struggle is interwoven with claiming the sovereignty. According to him, the government initiated a nation-wide rural rehabilitation during the transition phase after the fall of the Taliban. The Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) planned to run the rural reconstruction based on a National Solidarity Program with a close consultation with the Community Development Councils (CDCs) established in many villages and districts. The MRRD delegated the formation of more than 30,000 CDCs to 30 international NGOs, which have their own funds as well as staff and take ownership of the CDSs. The government problematized this matter in arguing that these international NGOs are being perceived as proxies of foreign countries that set the development agenda and goals of the country. However, NGOs emerged and began to provide services such as education, health and alternative livelihood in the conflict zones. Thus, the NGOs, addressing the immediate and short term needs of communities in all around the country, indigenized their presence and services and tried to “dispel their alien image” in the last four decades (see here for more about such efforts of NGOs).

Based on annual report of the non-governmental organizations, published by the Directorate of NGOs of Ministry of Economy 1863 NGOs were registered in 2018 and they implemented 2537 projects with the total cost of 876 million USD. However, 69% of the projects at the cost of 603 million USD were implemented by national NGOs. The same report highlights that NGOs have employed 85383 people, with around 1000 foreign nationals over the same period. This data shows that the NGOs’ staff makes 21% of total employment in 2018 and their role in poverty reduction and job creation is crucial. However, providing employment opportunity is not the only way how society benefits from the presence of NGOs.

Despite such socio-economic contributions by NGOs, the government gradually imposed limiting measures. These limiting proceedings included legislation, taxation, and deregistration of civil society organizations. This report underlines the recent tightening changes in the policies and the legislation concerning NGOs’ operations. The report suggests that as a consequence of such regulations the civil society, particularly NGOs, constantly suffers from closing of space and thus is a violation of the human rights and freedom of association that hinders sustainable development through limiting the representing role of the civil society and authorizing the political power to control them.

On the face of it the NGOs, which mostly implement the externally funded projects, are criticized for failing to maintain integrity, professionalism and accountability. As Omar Sadr a university lecturer in the field of political science at American University in Kabul attains “They were accountable only to the donors, rather than to Afghanistan.” Such perceptions of NGOs are widespread and can justify closing of space for NGO interventions. Moreover, there’s a danger for “lack of an inclusive concept, lack of legitimacy, and negative perceptions of CSOs among the public” as Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit underlines in an assessment on the role of civil society organizations in promoting good governance. Albeit this issue is not within the scope of this report.

Towards the GoNGOs in Afghanistan: a snapshot of the current situation

The government has hardly ever recognized the positive role of civil society organizations in terms of sustaining the economy and providing representation for the diverse groups. By contrast, as International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) underlines, President Hamed Karzai’s government (2001-2014) regularly attacked NGOs via media smearing and discouraging policies and laws in public saying: “The three great evils Afghanistan has faced in its history are communism, and terrorism, and NGO-ism”. Such perception about NGOs is evidently related to the disputed amount of fund granted for the local and international NGOs. Reports of the Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief (ACBAR) shows that the NGOs were benefited from only a small part of donor money. In contrast to ACBAR’s data, the Afghan government, unsatisfied with the funding of the NGOs, continuously claimed that the donors allocated significant amount of funds for the NGOs and thus, attempted to persuade the donors to transfer the funds to the ministries instead of the NGOs (see here for more detail).

Evidently, many of the conflicting political spectrums likely have similar views about the non-political, non-state actors including the NGOs. The current government increased the pressure on NGOs unprecedentedly as the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit stresses in one of its publications, concluding that the government apparently imposes control over non-state organizations and media at national and provincial levels. Also, his successor President Ashraf Ghani shared his approach in 2017, when he instructed the MoEc to establish a consolidated fiscal “One NGO Budget”, similar to the "one specific budget” of the government. Mr. Ghani justified this controlling measure as being appropriate for ensuring transparency.

Alongside attempts to control the NGOs’ financial flow, in recent years, the taxation policy has compelled NGOs to adjust their finance based on government requirements. The government demands NGOs to pay their staff income taxes – a process that is very complicated and prone to increasing administrative corruption.2

Over the last year, NGOs witnessed increasing pressure from the government. One of the most recent measures is the "Framework of Agreement and MoU with the NGOs", which was enforced by the office of Amrullah Saleh, the first vice president. The framework mentions ensuring of ‘value for money outcomes’ as a main goal. As a local news agency reports, prior to circulating this framework, the government halted the projects of many NGOs that run service or education programs through circulating a general order to all governmental agencies. Nevertheless, the local NGOs termed such general order as ‘interference in their affairs’ and demanded the government to abolish or revise the framework. (For more details, see here).

As Hameed Aziz, head of the Disabled Social Centre, protests, the framework limits NGOs’ activities, as “no donor will be able to raise funds in this manner and as a result all NGOs activities in Afghanistan will be stopped and this will be a huge injustice with the public”. Furthermore, the director3 of a human rights-promoting NGO, who asked the author to remain anonymous, added that for implementing a project on monitoring human rights, his organization submitted a request for an agreement with a relevant government sector according to the provision of the Framework of Agreement and MoU with the NGOs. However, they received no reply from the relevant authorities for five months and the donor cancelled the project due to this delay. He resumed his assessment, “the goal is to eliminate the NGOs”. A director of another NGO, who implements projects for women’s participation, raised the same concerns with the author, arguing that “in recent years the situation turned so tightening those civic activists are threatened systematically and they have to do self-censorship”, and added that “many of the NGOs’ projects about strengthening of the rule of law are stopped down”. She4 also asked her name not be disclosed.

Media reports confirm these concerns. Pajwork, a local news agency reflected the views of some NGOs in its report on 05 May 2021. According to this report, an NGO employee evaluates the recent measures as very “worrisome” as the general order and the framework have hindered many of the NGOs ongoing projects, while many of the new project agreements are not contracted as donors cancel them. The report highlights the extending drought all over the country, which requires urgent interventions. Despite such urgency, as this local news agency reports, many NGOs’ humanitarian projects have been discontinued.

The Framework of Agreement and MoU with the NGOs justifies and emphasizes the importance of the ‘government-organized NGOs (GONGOs). It classifies NGOs in four types and argues that “such categorization helps the government with understanding the nature of different NGOs and organizing them according to the needs of the society and, […] this [classification] clear the government goals of utilizing the non-governmental organizations for development of the society”5. As the mentioned local news agency highlights, the framework seems unlikely in the conformity with the enforced law concerning the NGOs. The framework, which explicates that such classification is not in accordance with the NGOs law, acknowledges this opinion and suggests that it “can be incorporated in the law in future”.

Moreover, NGOs are facing financial scarcity due to the withdrawal of the international organizations from the country. Ministry of Economy reports that the non-state organizations have suffered from the foreign aid fluctuation in recent years. NGOs implemented 5198 projects in 2016 (more than double the amount of 2018). These numbers depict that the fragile NGOs, as a think tank assessed in November 2020, are facing “increasing and unacceptable levels” of fiscal instability due to the downsizing of the international financial support and changing of the [donors’] policies as a reports of the Lessons For Peace underlines, donors ignore necessity of “a pooled funding mechanism that can provide the small grants needed by locally based NGOs and CSOs”, Skill gaps and lack of effective financial management of the local NGOs intensify such vulnerabilities. The government having no policy or mechanism for protection of diverse and flourishing NGOs, did not address this growing funding scarcity, but resolved 2267 NGOs from 2005 to 2017, whereby the disbanded NGOs did not send their annual activity reports to the MoEc. Moreover, from 2002 to 2017, the Ministry of Justice dissolved 4014 associations based on similar reasons. As Omar Sadr, an American University lecturer in Kabul, summarizes in an interview with a reporter of Foreign Policy, the government that is confronting with the escalating insurgency “…, rather than seeing the civil society as a partner, the government saw the civil society as a foe”. Yet, the unpropitious treatment of the government intensifies the pressures on the NGOs, particularly when the NGOs protest the mismanagement of international funds by ministries, such as fund donated for addressing the Covid-19 pandemic. The discouraging reaction of the government against that protest was “perceived by NGOs as motivated by the Presidential Palace’s interest in centralizing control over NGOs” (for more detail see here).

Legislating a new NGO- law

The Afghan government evidently enforces the shrinking measures by approaches, encompassing the NGOs-Law and many more legislations including media laws, taxation laws, access to information law and the laws concerning counterterrorism, laws on assembly and law on associations. This part of the report investigates the implications of the most recent draft NGOs law and some of its bi-laws, which regulate registration and reporting of the NGOs activities. Furthermore, the report investigates the conformity of the law with the human rights instruments and the country’s constitution.

The Ministerial Cabinet of Afghanistan discussed an amended NGO-law on 6 July 2020 and did not approve the bill due to (what they described as) some shortcomings in it and instructed the Ministry of Justice to revise the bill. However, as a note of the Ministry of Justice about this process highlights, the cabinet emphasized that the revised version of the bill should have some provision distinguishing between domestic and foreign NGOs, clarity in their structures and functions, spending the budget and the ceiling of their staff salaries and the regulation of responsibilities of the departments of the NGOs”. A report of Sarwar Danesh, second vice president, about the bill also mentioned on 12 August 2020, that the draft NGO-Law needed revision after consultation with the national and international organizations. The Ministry of Justice6 and Ministry of Economy submitted an amended version of the bill to the cabinet in December 2020.

Along with the draft-law, the government of Afghanistan drafted nine regulations for enforcing it. All these documents evidently shrink the working space for NGOs. The due process and due times in these documents are ambiguous and the Ministry of Economy (MoEc), the responsible government agency for regulating the NGOs, can deny licenses or their extension. Such an extension would be based on the new law obligatory for every five years. Such tightening obligations unprecedentedly press the NGOs.

The status of non-governmental institutions in the laws of Afghanistan

As experts such as Frits Hondius underline, beside the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, other germane instruments are also enriched with the provisions on the fundamental freedom of assembly and activism, which safeguard the rights and security of the non-state actors. Yet, the UN general assembly passed a resolution on 8 March 1999, titled “Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedom”.

Article 5 of the resolution provides that “everyone has the right, individually and in association with others, at the national and international levels: to form, join and participate in non-governmental organizations, associations or groups” and communicate with such organizations. Furthermore, Article 18 of the same resolution emphasizes those non-states organizations’ role in the democratic process as well as in the promotion of human rights as a key factor for progression.

The government of Afghanistan is obliged under the aforementioned laws to provide an enabling ground for the non-state structures. Article 35 of the country’s constitution provides that “the citizens of Afghanistan shall have the right to form associations” and article 36 guarantees that the people of Afghanistan “shall have the right to gather and hold unarmed demonstrations […]”.

In practice, the government registers the non-state institutions under two categories: The laws differentiate between non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and ‘Associations’, which are regulated respectively by the 2005 Law on non-governmental organizations, administered by the Ministry of Economy (MoEc) and the 2013 Law on Association, administered by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ).

NGOs and recent legislations

According to experts of nonprofit laws, the draft law concerning the NGOs is problematic, as it does not encourage an open sphere for civic participation and the following shortages are noticeable:

Undue times and process

The first Article of the draft law7 provides that it regulates the NGOs affairs including the registration, establishment, monitoring, evaluation and maintaining transparency and coordination and cooperation in the activities of the NGOs. Article 11 and 12 of the bill regulate the registration process and list the necessary documents and data for licensing a new NGO. This includes a title, logo and the statute of the organization and details on the founding members.

The original bill provides no “due time” for proceeding of the NGOs registration applications by the MoEc. The revised article 10 of the bill provides a five-day period for the Provincial Departments of the Ministry of Economy to submit the application to the Ministry of Economy’s headquarter in Kabul, “after filling the gaps and addressing the defects”. Despite this reform, this part of the draft yet retains undue regulations, as the law does not explicitly link the due process with proceeding of the applications. It rather narrates that the ministry’s branches shall send the applications within five days to the ministry after they collected all the necessary documents. Consequently, the provincial departments may delay collecting and scrutiny of the documents, as there is no due time for regulating this process. Furthermore, the term of “after filling the gaps and addressing the defects” sounds inexplicit. The law does not define what “the gaps” and “the defects” mean. As watchdogs such as Amnesty International underlined, such ambiguities can give grounds to despotic interpretation of the law and misusing of the authorities.

Article 14 of the bill regulates that after collecting registration applications, the Department of Coordination of the NGOs (in the MoEc), shall send the collected applications within 10 days to the Evaluation Commission of the Organizations, composed from the representatives of the MoEc, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, NGOs umbrella organization and the women’s umbrella organizations. Again, the law does not determine the due time of the applications’ review by the Evaluation Commission of the Organizations. Such uncertainty can exacerbate the management of this Commission’s tasks, because maintaining coordination among the inter-ministerial commission without a due period and due process, might be controversial and delay the establishment of the NGOs.

Renewal of the NGOs licenses

The bill requires that NGOs shall apply for renewal of their license every three years (Article 18). Given continuous supervision of the NGOs by the MoEc, through initial registration, evaluation, annual report (Article 49); financial audits, publishing of their annual financial statements (Article 34); and receiving and approving their activities plans; the renewal of the NGOs’ license is an overburdening activity and indeed a means of controlling, as Amnesty International underlines in its statement.

The restricting rules

The current enforced law on NGOs lists a ten-category of the “unauthorized activities” that an NGO shall not perform. For example, Article 8.7 prohibits the “use of […] financial resources against the national interest, religious rites and religious proselytizing” and in clause 8.10 the law prohibits the “performance of other illegal activities”. Neither this law nor the bill defines the terms such as “national interest, religious rites and religious proselytizing” and these clauses of the Article 8 are subjected to interpretation by the authorities and can be used against the NGOs or forced the non-state actors to limit their activities precociously. Hence, such “overly broad grounds” may be used to disband independent and “critical NGOs”.

Moreover, Article 8.8 forbids the NGOs’ “participation in construction projects and contracts.” This rule also limits the rights of the NGOs constituencies to non-profit construction projects.

Dissolution of NGOs

It seems that the law provides no judicial protection for the NGOs as the government can dissolve an NGO based on the provisions of the law, whenever the NGO does not apply for the renewal of its license of operation or does not send its reports on due time. The Ministry of Economy strictly enforced this power. Beside the above-mentioned figure of the dissolved NGOs, MoEc deregistered 320 NGOs only during 2018, as they failed to submit their activity reports based on requirement of Article 31 of the enacted NGOs law. The number of the dissolved NGOs is equal to 15% of all active organizations and far greater than the 223 new registered NGOs during the same period.

Furthermore, article 46 (3) of the draft law stipulates that an NGO can also be dissolved if any government department or citizens submit a written and documented complain about its illegal activities.

The Evaluation Commission of the Organizations, which is a semi-inter-ministerial commission, decides about the registration of NGOs, renewal of their licenses or dissolution of the organizations. Article 15 of the law obliges a five-member evaluation commission, composed from representatives of the MoEc, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Finance, NGOs’ umbrella organizations and the women network. Moreover, the law indicates that the secretariat of the commission shall be retained with the NGO Department of the Ministry of Economy. Given number of the Commission members and the division of the authorities, it is evident that the bill codifies an imbalanced power between the representatives of the NGOs and those of the government.

Articles 26 and 27 of the bill regulate establishment of umbrella and coordination organizations of the NGOs. According to Article 26, the umbrellas of the organizations shall have at least 10 member NGOs. The umbrellas can be registered after approval of the respective governmental sectorial officials and approval of MoEc. Furthermore, the law instructs that the chairperson and the deputies of the executive committee of the umbrellas shall be elected for one year (Article 26.3). Based on Article 27, the Coordination Organizations shall also be registered by the MoEc. Binding of the formation of an NGOs umbrella to the prior approval of the state sectoral entities and the MoEc and governing internal management of such coordination bodies, indicate that the MoEc extends the controlling measures to the coalitions. Likewise, an NGO is obliged to inform the MoEc within 30 days if it acquires membership of an international organization (Article 28).

Governance of the NGOs by interference in their internal management

Chapter five of the draft law regulates the internal governance of the NGOs. Article 45 affirms that all NGOs shall have a board of directors and an executive board. Article 46 affirms that the board of directors, composed of at least three persons, act as the decision-maker of the NGO. Article 46 (2) lists the qualifications of the board members such as completing 18 years of age, holding at least a bachelor’s degree, having at least three years of experiences, not being sentenced to dispossession of civil rights and having no conflict of interest with the NGO. The law requires the founders to elect the members of the board of the directors for a period of two years. However, they can be re-elected (Article 46.3). The law extends similar interferences of the government to the Executive Board of NGOs in Articles 47 and 48 and authorizes the MoEc to regulate the internal management of the executive board by defining the structure of the board, by limiting the working period of the members to three years and by defining the mechanism for employment of new board members. Furthermore, Article 60 of the bill obliges the NGOs to archive the documents of their managerial plans and activities for “up to seven years”. Such provisions may violate the privacy and independence of the NGOs and the privacy of the individual employees. In Afghanistan there are customary civil society groups, hence such provisions prevent the experienced people without a bachelor’s degree from having an active role.

The bill requires the NGOs to adjust their internal policies to the provisions of the legislations such as Labor Code and regulations of MoEc. Nevertheless, application of such internal policies is subjected to prior endorsement by the Evaluation Commission of Organizations (Article 56). As a note of ICNL for the Civil Society Joint Working Group (CSJWG) underlines, this compulsory rule interrupts the freedom of association, because developing of internal policies are the outcomes of per se free-from-coercive supervision debates of the NGOs and their constituencies, which might be a reaction towards the government policies and laws.8 If the NGOs are not able to manage their own affairs, they would indeed have no freedom as the bill allows the state to have “arbitrary power” to intervene with the NGO’s affairs and activities. Consequently, the minimum necessary standards for an open civic space will be faded out.

“Confidentiality”, legislated in article 63 of the bill, is another undefined provision, which threats the freedom of NGOs, as the law states that “members of the Board of Directors, members of the Executive Board and other staff of the NGO shall not disclose or transfer the conditional historical, cultural or military [matters]”. Therefore, this obligation restricts the initiatives of the NGOs about research or investigative reports on cultural and historical places and issues and prohibits open debates about cultural policies and plans.

Ironically, the law stipulates that NGOs shall not only comply with such controlling and interference, but they shall also provide necessary facilities for supervision of MoEc. For example, Article 49.3 binds the non-state organization to facilitate not only the Ministry of Economy’s supervision, but also monitor “the relevant sector administration”.

Article 55 implies that all equipment of the NGOs shall belong to the government, because it reiterates that in case of the NGOs disillusion, the moveable and immoveable assets of the NGOs shall be donated either to another NGO, or “the movable and immovable property of the disbanded organization shall belong to the relevant sectoral administration”. Enforcing of temporary number plate for the NGOs’ vehicles according to this law resonates the same dominance. Article 62 of the law requires that NGOs’ vehicles shall title temporary plate numbers with a specific pattern. Exceptionally, the law provides that only in case this specific plate causes a threat, the NGO can use personal (civilian) vehicle registration plate.

Article 65 of the bill authorizes the High Evaluation Commission with the power to judge if an organization perpetrates unlawful actions and […] the Commission can issue fines or dissolve the NGOs. The law indirectly bans NGOs right to judicial appeal against such decisions due to the omission of a specific paragraph. Thus, it positions the NGOs in a vulnerable status against the state power.

Article 68 of the law provides that the MoEc shall legislate procedural by-laws. Nevertheless, the law provides no mechanism for incorporation of the NGOs concerns about such procedural regulations. The website of the MoEc depicts that the ministry has already drafted nine regulatory by-laws, officially entitled: procedural law on registration and dissolution of the NGOs; procedural law on internal governance of the NGOs; by-law on supervision of the banking of the NGOs; procedural law on coordination of the NGOs’ programs and projects with the sectorial governmental offices; procedure of the NGOs’ operation in the provinces and regulation on counter-terrorism measures. The MoEc recently published a Policy for Prohibition of Money laundry and Funding of Terrorism. This policy requires NGOs to open a separate account for each project. Yet, the NGOs shall obtain an approval from the MoEc for opening an account and closing it. Accordingly, banks cannot open or proceed any transaction without the allowance of MoEc and shall not provide ATM cards for the NGOs’ accounts.

A skim of these procedural by-laws shows that all serve as means of controlling NGOs rather than protecting them or providing services for them. As mentioned above, such “conservative changes” together with the introduction of bureaucratic regulations are burdensome for both, NGOs and government officials, leading to the cancellation of many projects.

The Impacts of closing civic space on NGOs

Civil society organizations including NGOs provide a public sphere for free and open exchange and enable people to have a voice in agenda setting and to raise their concern about the policies and the matters of their economic sustainability. In contrary, closing of the public sphere can harmfully limit the role of social actors, such as non-state groups and organizations. Scott Peterson, an analyst of the Christian Science Monitor, summarizes such conservative setbacks as follows: “Afghan government is pushing more Taliban-style policies”, because “the media and NGO laws […] imposed stricter government controls”.

Nevertheless, the negative effect of shrinking the civic space is a “serious threat to the existence of civil society”, as Amnesty international warned on 27 July 2020. In addition, the International Center for Non-for-Profit Law reports that currently there are 1818 active domestic NGOs and 268 INGOs as of January 2021, while the MoEc has de-registered 3371 NGOs since 2005, because they could not report to the ministry. As of January 2021, the Ministry of Justice also terminated 1600 associations based on similar motives since 2013.

The current enacted law and the bill explicitly prohibit NGOs from taking part in construction projects. In the war-torn cities and villages, where a large scale of the infrastructures was destroyed, people have no access to education or health facilities. Such barriers and the other restrictive measures against the NGOs, may delay the economic and human developments of the country. Some research underlines the harmful effects of a closed social space on the development of the underserved areas and communities. For instance, Naomi Hossain asserts that, whereas the new legislations shift power from civic actors to the politicians, i.e. the governmental authorities, civic space has been limited drastically in the recent years. This trend makes the communities, which are dependent on the aids, more vulnerable. In practice, such shifts of power may negatively affect the development of peripheries, as the politicians may prioritize other interests. Given civil society has supported the development of the underserved and disempowered communities in many contexts of the fragile states such as Afghanistan, the barriers against the non-state activist groups are unlikely to be in favor of the marginalized groups. In such a circumstance, “economic crises are more likely setting where civic space” is closed. Furthermore, empirical studies prove that where civic participation is closing, it is impossible for development to have a chance for inclusive and sustainable results (see the book of Hossain et al. here).

It is apparent that NGOs will have no meaningful independence and freedom in planning and implementing their activities. Therefore, the NGOs have no other option rather than following compliance and compromise. Evidently, in such a situation, NGOs cannot take part in a free civic space and practice a free-from-coerce social sphere for open exchange and representation in order to influence the government policies or raise the socio-economic issues as experts such as Vosyliute and Luk assert in a study for the European Parliament.

The draft NGO law and the obligations of Afghanistan under Human Rights Laws

Having reviewed several NGOs-laws, Braunmiller of the Protection Project, maintains that it is vital for NGOs to be able to manage their internal governance independently, including the freedom to draft the necessary internal by-laws, to decide on their structure, policy making, fundraising and financial management. Article 17 of International Covent on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) explicates the rights to privacy and protection of correspondence and ensures the freedom of non-state organizations. The UN Human Rights Committee’s General Comment No. 31 (9) clarifies this further in emphasizing that the right to privacy is applicable to both individuals and organizations:

Although […] the Covenant does not mention the rights of legal persons or similar entities or collectivities, many of the rights recognized by the Covenant […] may be enjoyed in community with others.

Taking this into account, the governments cannot interfere in the archives, or governance and premise of an NGO unless under a due process while NGOs can maintain their privacy and ensure transparency and accountability (see for details the manual of The Protection Project).

Afghanistan is a signatory to many human rights conventions and treaties, inter alia the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), both of which are enshrined with many principles that aim to ensure freedom of association.

Despite of the Afghan state’s commitments to such human rights instruments, civil society is at risk of losing its authority due to the change of regulations, to smear movements and to other pressure mechanisms. Hence, the bill probably violates against the provisions of the human rights laws on associations, because it obliges the NGOs to accept the supervision of the government, or face sanctions and even dissolution. In addition, the bill limits the freedom of the NGOs policymaking and project planning, even though freedom of association, assembly and freedom of expression and access to information are amongst the fundamental rights, protected by the Universal Declaration of the Human Rights, ICCPR and ICESCR (see Amnesty international statement). The following are a few of the articles of the UDHR, ICCPR and ICESCR, which are violated against or limited by the bill.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

UDHR provides in Article 2 that “everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration […] and no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international”. Article 19 stresses that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression” and Article 20 ensures “the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association”.

The NGOs bill requires that non-state organizations’ founders and board members shall hold a specific university degree and reach adult age. These codified restrictions on who is allowed to find an organization violates Article 2 of UDHR by distinction of the undergraduate and juveniles. Furthermore, the government power to take part in the internal meetings of the NGOs and control their internal governance and policymaking process contradicts Article 19. Further, the bill enhances the power of the state with denying registration of the civil society organizations, or halting renewal of their licenses or dissolving NGOs. Such extensive power to govern the formation and the lifecycle of the non-state organizations are in conflict with the provisions of Article 19 and 20 of the UDHR.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

The bill particularly and explicitly overrides the rights to independence of expression and association provided by ICCPR (see Amnesty international statement). For a core value enshrined in it, is direct or indirect (through election of the representatives) participation of the citizens in civil society and political affairs. In fact, this fundamental human right is also well-known as freedom of speech, as experts such as Stillman construes.

Article 17 of ICCPR provides that “no one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence”, and Article 19 guarantees that “everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference” and also to “freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice”. Furthermore, Article 21 orders that “the right of peaceful assembly shall be recognized. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right […]”, and Article 22 explains that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests”.

These provisions, according to the analysis of the experts, mean that the governments should refrain from undue interference in NGOs’ internal affairs, including their policymaking and meetings. (See the handbook of the Protection Projects).

The report of ICNL on the non-state actors’ situation in Afghanistan highlights the recent “barrier to entry” And arbitrary deregistration of NGOs. Since the bill restricts the establishment of NGOs to a certain group of people, denial of the right to assembly and association from many other potential interest groups is in conflict with the provisions of ICCPR on such rights.

Moreover, the draft NGOs-law’s limiting clause is very broad and requires that NGOs shall not engage in actions, which are allegedly against the national interests, against the religious values or do not respect the confidentialities. Based on Article 22 of ICCPR, NGOs shall not involve in activities, which violate in a democratic society […] the interests of national security or public safety, public order, protection of health or protection of the rights and freedoms of others (Braunmiller 2014: 23). National interests and religious values, however, are not defined and are open to interpretation

Furthermore, Amnesty International states that freedom of expression is vital for “the work of human rights defenders and NGOs”, as “under interference” by the state these NGOs cannot assemble and organize meaningfully for monitoring and promoting of human rights. NGOs, as associations of people and collective exercise of the freedom of opinion, serve as platforms, where their members represent certain social groups. Furthermore, NGOs may undertake initiatives that support socio-economic development of their constituencies, and they can support democratic process and maintain the “balance of power” (see the handbook of The Protection Project). In contrast, once the NGOs’ members understand that the law allows the government to take part in their internal meetings or have access to the documents and policies of their organizations, they cannot openly share their concerns. Thus, such a law explicitly tightens controlling of the fundamental right to the freedom of expression.

The Constitution of Afghanistan

The Afghanistan Constitution 2004 guarantees fundamental rights of freedom of association, liberty of opinion, and access to information, correspondence, rights to work and privacy in the preamble and many of its articles. The Preamble affirms that “[…] the people of Afghanistan, […] 8. For creation of a civil society free of oppression, atrocity, discrimination, and violence, based on rule of law, social justice, protection of human rights, and dignity, and ensuring fundamental rights and freedoms of the people, […] have adopted this constitution […]. Article 7 of the constitution requires that “the state shall abide by the UN charter, international treaties, international conventions that Afghanistan has signed, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”.

Furthermore, chapter 2 of the constitution on the Fundamental Rights and Duties of Citizens ensures nondiscrimination while Article 22 and Article 24 stress that “liberty is the natural right of human beings”. Article 34 declares that “freedom of expression is inviolable. Every Afghan has the right to express his thought through speech, writing, or illustration or other means, by observing the provisions stated in this Constitution. Every Afghan has the right to print or publish topics without prior submission to the state authorities in accordance with the law”. Most relevantly, article 35 affirms that “the citizens of Afghanistan have the right to form social organizations for the purpose of securing material or spiritual aims in accordance with the provisions of the law.”

A comparative reading of the NGOs bill and the Afghanistan Constitution may indicate many unconstitutional provisions, which shrink the freedom of expression and a fair privacy of the associations. The International Center for Non-for-Profit Law highlights three legal barriers in this bill against NGOs in terms of registration, activities and advocacy. Denying of NGOs’ supportive registration process; obligating NGOs to submitting of their plans to the MoEc and other authorities prior to beginning of their projects and restricting their activities by labeling them as political or against the national interests are some outcomes of such barriers. Indeed, such provisions, which shrink or close the space for the non-state actors are in conflict with many fundamental rights ensured in the constitution, including civic and opinion freedoms.

Conclusion

This analysis of the draft law concerning the non-governmental organizations of Afghanistan reveals an intension of the government to increase its power significantly by supervising and controlling NGOs. The bill authorizes the MoEc with a wide range of interference in registration, access to private documents of NGOs, influence over their policy making and internal governance, banking and development of the strategies, projects and programs. Accordingly, governmental employees can take part in the internal meetings of the NGOs or monitor and stop their activities. This law severely tightens the already shrunk civic spaces for freedom of non-state organizations and reduce their effectiveness as independent social actors. This normalizes the preferences of the sectorial government policies, as it requires the NGOs to compromise with the governmental policies and priorities.

If passed, the bill would unnecessarily restrict the space of civil society organizations and threaten their existence. As Amnesty International warns, such approach is explicitly in conflict with Afghanistan's obligations under international human rights law. The comparative analysis of the bill with the provisions of Afghanistan’s constitution and human rights laws indicates that the draft is unconstitutional and breaches the UNDHR and other human rights laws, to which Afghanistan is a signee. However, the Afghan state is constitutionally committed to respect, protect, promote, and realize the right to freedom of association and expression and to create a safe and accessible environment for human rights defenders and civil society organizations.

Moreover, freedom, openness, and security of NGOs, as a form of public sphere for civil society, enables citizens to participate in sharing and receiving information as well as partaking critical debates and creating of policies on behalf of non-state actors. On the other hand, the legal analysis of this report highlights the negative effects of shifting the power from civil society to the government. Evidently, wherever the state limits the role of the non-governmental organizations, the country is prone to despotism, corruption, and non-democratic laws (see Act Alliance analyses). Indeed, such a circumstance could not prospect a resilient and inclusive economic development.

Footnotes

1) Such donor-driven agenda for democratization and advocacy, provided an enabling space for civic actions and beside the NGOs, Jamiyat (Associations, other form of the civil society organizations increased quantitatively also in the last two decades. The Law on Associations, Official Gazette no. 1275 of 2017, defines defines a Jamiyat , ‘ Association’, as non-political, and not-for-profit social organizations (communities and associations) that are voluntary associations of natural or legal persons formed in order to achieve social, cultural, scientific, legal, artistic and professional goals, in accordance with the provisions of the law. (Law on Associations Article 2(1)). The Ministry of Justice of Afghanistan, regulating the associations based on this law, has registered 3075 associations (Jamiyat) as of 2019. The law Article 13 (3) of the same law requires that the Associations shall apply for the renewal of their license every three years. According to the initial draft of the Law on Associations (OG 1114, 2013) only court could dissolve an Association. This power was shifted to the Ministry of Justice based on the amendments to the law in OG number 1257 and thus, the Associations have lost the judicial protection.

2) The government presses also the associations and Medias through taxation policies. In 2017, the government obliged the printed media to clear their taxation within 6 months or they should have to stop their activities. Nai Supporting Open Media in Afghanistan, a media watch organization, reported in November 2019 that owing to the government taxation policy and other financial problems, 225 media outlets (including 7 TV and 15 Radio channels) have had to close their activities in the recent five years.

3) An online interview with the director of a Kabul based NGO, on 12.05.2021.

4) An online interview with the director of a Kabul based women rights-oriented NGO on 10.05.2021. She is also very active in working with the media and develops regularly news outlets about the situation of the women’ rights.

5) The Framework provides seven different arguments for categorizing the NGOs. However, the most detailed reason is highlighted in this report.

6) An employee of an NGO sent a copy of the report to the author. The MoEC published also a brief of the Ministry of Justice about this process in its website (See for more detail in Dari: https://moec.gov.af/dr/%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%87%D8%A7)

7) A copy of the draft law is available for the author by an employee of an NGO in Herat.

8) Abdullah Ahmadi, ex-chairperson of the CSJWG in an interview with the author on 11.03.21 said that the draft law challenges the Afghan civils society and they asked ICNL to provide a review for the NGOs.

The author would like to express deepest appreciation to Kava Spartak for editing and, Jost Pachaly, Gita Herrmann and Felix Speidel for reviewing and commenting on the report.